Antonio Larrosa is the current president of KDE España and he and I have been friends for quite some time now. It may seem logical, since we both live in Málaga, are passionate about Free Software in general, and KDE in particular. But in most other respects we are total opposites: Antonio is quiet, tactful, unassuming and precise. Enough said.

But that is what is great about Antonio; that and the fact he is very patient when troubleshooting. I know this because he has often helped me out when I have unwittingly wrecked my system by being an idiot and installing what I shouldn't. When he quietly muses "¡Qué cosas!" (which roughly translates to "That's interesting") you know you've messed up good.

Antonio will be delivering the keynote on the 23rd of July at this year's Akademy, so I caught up with him and asked him about stuff I didn't already know. Turns out that is quite a lot.

Enjoy.

Antonio Larrosa: Hi!

Paul Brown: Good morning Antonio! Long time no see.

Antonio: Good morning! Yes indeed. Heh heh!

[We had talked the day before]

Paul: I think you are aware that the other keynote speaker is Robert Kaye from Musicbrainz, right?

Antonio: Yes, I know. It's quite an honor to have him at Akademy this year and I hope to meet and talk to him, since I love the Musicbrainz project.

Paul: I understand you worked on a project that ties MusicBrainz to a KDE app...

Antonio: Actually, it's not really a KDE app. Some months ago, I learnt about Picard (which is MusicBrainz's music tagger) and I wanted to use it, but it lacked a few features that were important to me. So I had a look at the code and was excited to see it was using Qt, so I decided to contribute to it.

Paul: What did you change?

Antonio: I fixed a small function in Picard's script language to better support multivalue tags. I also improved the support for cover art, like allowing drag & drop from a web browser, a nice way to see differences between old and new covers before saving the changes, better visualization of albums with different covers in different tracks, etc. The fact that it's written in Python and has a very good design made it easy to start contributing fast. The community was quite friendly too, which always helps.

Paul: You have also contributed to Beets. What is that and what did you do?

Antonio: Yes, Beets is (I quote from its web page) "the media library management system for obsessive-compulsive music geeks". Who wouldn't like to use it with that description? It has auto-tagging support which also uses Musicbrainz's metadata (like Picard), but the tagging is not as advanced as Picard, so I tried to improve its multivalue support so at least it could read and perform queries on all tags written by Picard. Apart from very simple patches, the important patches I submitted to Beets are still in the review queue, but I hope they'll get merged soon.

Paul: You are a mathematician, not a programmer, by training. Correct?

Antonio: That's correct.

Paul: How did you get started in programming?

Antonio: I got started when I was around 7 or 8 years old. I had a Dragon 64 and it was almost impossible to find games for it. So, when I got tired of playing the ones I had, I learned to write my own, and found it was great.

Photo by Miguel Durán - Dragon 64, CC BY-SA 2.5, Link

Paul: BASIC?

Antonio: Yes, BASIC and a bit of assembly.

Paul: What sort of things did you program on the Dragon? Games? Anything to do with school work? I remember writing a function plotter for the Commodore 64, for example.

Antonio: Really? That's interesting, I did a graph plotter for the Dragon and one of those old text-based RPG games. But no, not really school-related.

Paul: What did you have to do in your text-based adventure?

Antonio: I don't remember very well -- I was around 8, but it was probably something related to killing dragons.

Paul: Of course. If I remember right, the Dragon was quite limited even for the day. What did you upgrade to next?

Antonio: A 286 running at 6Mhz with 640 KBs of RAM and a great big 20 MBs hard disk.

Paul: 20 MBs! Did you have the sensation of: "Wow! I'm never going to fill that up."?

Antonio: Of course! There was plenty of space for so many applications in there!

When I was 12, I created a calculator that parsed mathematical expressions, and then calculated and enunciated the result through the sound card

Paul: How old were you at this stage? Were you already at university? Because those machines were expensive! I don't see a parent buying a 286 for a twelve-year-old.

Antonio: Not at all, I was still at school, maybe 10 years old or so. But I have an older brother who would have been about 15 by then. My father, being a car plater, never used computers, I would go as far as saying he hated them, but he had a good eye for seeing what would be important in the future for us.

Paul: What did you use the 286 for? More games?

Antonio: Yes, I have to admit that I played games when I was 10. But also I learned Pascal and Assembly. When I was around 12 (just before high school) I created a calculator that parsed mathematical expressions, and then calculated and enunciated the result through the sound card. In order to do that, I used Assembly, learned about IRQs, DMA, memory addressing with segments and offsets... It was quite fun. I even had to do my own audio editing application, in order to cut my voice saying different numbers which would then be concatenated together by the calculator.

Paul: Wow! You did all that when you were 12 and on a 286?

Antonio: Yep.

Paul: What did you do in high school? Hack into WOPR?

Antonio: Hah hah hah! No. I wrote and refactored up to 7 times a general purpose object oriented database that I used to store the contents of all my floppy disks so I could search where a file was quickly. Note that I learned about the word "refactor" much later, but that's basically what I did, although at that time I called it "throw everything away and rewrite it better".

Paul: Of course. After all, you probably didn't know about version control then. What year was this?

Antonio: Maybe 1992 or 1993.

You could say that Doom influenced my choice of careers.

Paul: When you say floppies, are we talking about the real thing, those 5 and 1/4 things that often got chewed up in the drive?

Antonio: Yes! 5 1/4 and 3 1/2, in fact. When I started using the application to catalogue CDs, I remember having lots of problems with memory addressing since data structures flooded over segment boundaries. After all, it was a windows 3.1 application.

Paul: Ok. You're now at university, but you decide to go for Mathematics instead of Computer Science. Why?

Antonio: I read back then a now defunct magazine called Dr. Dobbs Journal. One of the special issues was dedicated to 3D rendering as used in games such as Doom. I saw that you had to know a lot of mathematics to understand the articles, and I thought I could learn by myself what was interesting to me from computer science (as I had been doing for many years) but mathematics was different, so I decided to study mathematics.

Paul: Doom influenced your choice of career?

Antonio: Yes, you could say that in a way, it did.

Paul: Why am I not surprised. When did you first hear about free software?

Antonio: I was finishing high school, and my brother, who studied computer science, came home with a bunch of floppy disks containing a new operating system. It was Linux 1.x.

Paul: Linux 1.x! So you guys installed it?

Antonio: Of course! If I remember correctly, it was around 1995 and it was a Slackware distribution.

Paul: Let me guess, you had to dig out your monitor manual and work out the vertical frequency.

Antonio: Yes, finding out the specific horizontal frequency of your monitor was a nightmare, indeed. I also remember having troubles with the 20th something floppy and having to start again, inserting and swapping floppies. But I was excited that I could for the first time write a program in which I could reserve a block of memory of more than 64 KB of memory and just address any byte in it without caring about segments and offsets. Definitely those were other times.

Paul: Did you install it on your 286?

Antonio: No, by that time I had a 486.

Paul: Were you aware of the "Free as in Freedom" thing back then?

Antonio: I read about it, but of course I couldn't understand the importance of "Free as in Freedom" until some years later. At that time, I only knew that I had the sources for everything that run on the computer, and that allowed me to change things to make them work the way I wanted.

Paul: That was exciting, wasn't it? So different from the constraints of other OSes.

Antonio: Exactly! At that time I had an electronic keyboard with a MIDI interface which I used to connect to my windows 3.1 system. The keyboard didn't support the General MIDI standard, but windows 3.1 had configuration parameters so I could configure it to work. Once Windows 95 was released, they removed those options so my piano wouldn't work any more. But I had this operating system with all the sources for the MIDI player (playmidi at that time). You can guess what happened.

Paul: So when did you discover KDE?

Antonio: The playmidi author didn't accept my changes because the sources differed a lot from what I used. I sent him a real letter with an actual floppy disk since I didn't have Internet access back then. He didn't release any newer versions with different implementations either. So I decided to do my own MIDI player, but instead of doing a terminal application I wanted to make an X11 app. I looked through the options, which at that time included Athena widgets, Motif, and so on. I found KDE searching for alternatives, and absolutely loved it.

Paul: And the rest is history...

Antonio: Yes.

Paul: What projects have you worked on, apart from your personal MIDI thing?

Antonio: Apart from KMid, I worked on KPager, which was the application that showed the virtual desktop miniatures, and parts of kdelibs, specifically the library version of KMid and the icon loader classes which I maintained for several years. I also worked on all sort of applications fixing bugs everywhere I could.

Paul: Your day job is being a developer at SUSE, right?

Antonio: That's right.

Paul: Is there any overlap between your job at SUSE and KDE?

Antonio: To some extent: I'm a SLE (SUSE Linux Enterprise) developer working in the desktop team. As you may know, SLE is a term that refers to all the enterprise oriented distributions made by SUSE. The latest release only includes the GNOME desktop, so much of my work at SUSE includes fixing issues in GNOME. On the other hand, openSUSE not only comes with both KDE and GNOME, but openSUSE Leap uses KDE by default, so I also work on fixing KDE issues too.

Paul: How many people work on KDE at openSUSE?

Antonio: Really not as many as I'd like. In general there are around 10 people, but actively working everyday on KDE at openSUSE there are around 4 or 5 persons. If anyone reading this wants to help. We're always at the #opensuse-kde channel on Freenode.

Paul: What about the openSUSE community, volunteers?

Antonio: In general, everyone contributing to KDE packages in openSUSE is a volunteer. As I said, there are around 10 maintainers, of which I think only 2 or 3 are employed by SUSE. Fortunately, there are more community packagers helping with the near 1000 KDE/Qt packages available in OBS.

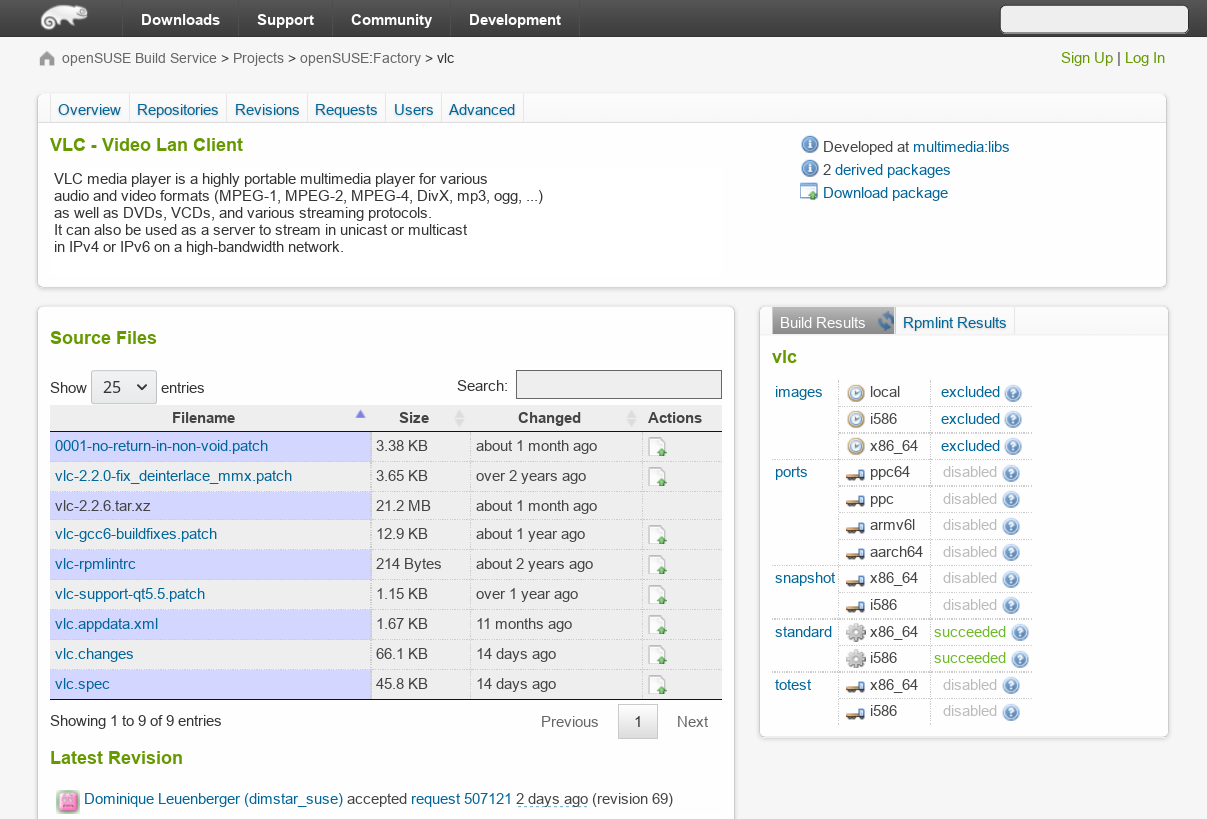

Paul: This is the openSUSE Build Service thing?

Antonio: Yes. That's where we build all openSUSE distributions (Leap, Tumbleweed, Krypton, Argon, etc.) and where we develop all packages that users can install in their openSUSE systems from software.opensuse.org.

Paul: And unofficial packages too, right? I mean, if there is something that is not in the official repos, you can look for it on software and it fetches and installs it from OBS, yes?

Antonio: Yes, that's right. Users wanting to try the latest version of any package can search for it on software.opensuse.org and install it from there with a one-click installer.

Paul: I imagine there is a warning that pops up when you try to install from an unofficial repo.

Antonio: Yes. Installing unofficial packages is not recommended in general, since users can break their systems if, for example, they install a buggy glibc library, but it's possible to do so.

Paul: Let's get back to the reason we are doing this interview: Is this your first keynote at an Akademy?

Antonio: Yes, it is and I'm really very honored.

Paul: Have you thought what you want to talk about?

Antonio: I have a general idea. I want to talk about KDE and its ecosystem, everything that KDE is, and where KDE is at this moment/where we want it to get to.

Paul: "Ecosystem" as in the people working on it? Or the state of the tech?

Antonio: The state of the communities around KDE compared to KDE's own community and how we could improve it and make it grow.

Paul: When you say "the communities around KDE", what communities are you referring to?

Antonio: Distribution communities, the Qt community, communities from other projects that use KDE libraries...

Paul: What is one thing we can learn from them?

Antonio: Well, something I learned is that we (KDE) are not alone and everything we do affects other communities, while at the same time, everything they do affect also our beloved KDE community. If we want to prosper, we all need to learn to work with others and let others work with us so we all benefit from the shared work.

Paul: And is that not happening?

Antonio: That is happening, but there's always room for improvement. For example, we at openSUSE made a terrible job at requesting help from KDE developers some months ago and the request was interpreted by some KDE developers as a threat. Fortunately I think we solved those problems nicely and the misunderstanding is fixed now. But we really should have done a better job at communicating better.

I started going to Akademys before they were called Akademys.

Paul: Let's talk about the tech for a moment. What is, in your opinion, the most exciting KDE project right now?

Antonio: Well, that's a personal opinion, and you might say that I'm cheating, but I'd say that the whole KDE Frameworks is great. If you ask me for an application, I'd probably say Mycroft. The author has a talk scheduled at Akademy that I hope to see.

Paul: Ah yes, the Free Software alternative to Alexa-like AIs.

Antonio: Correct.

Paul: Have you been to all the Akademys?

Antonio: Not all, but nearly. I started going to KDE meetings before they were called Akademys. My first one was KDE-Two, in 1999.

Paul: Wait... Was that what it was called back then? Just "KDE" and a number?

Antonio: Yes, the first meeting was "KDE One", the second "KDE Two", and so on.

Paul: How did it change to "Akademy"? Were you in that meeting?

Antonio: Well, it wasn't any kind of "special meeting". After the "KDE Three" meeting in 2002, we had a get-together in an old castle in the Czech Republic in 2003, so it was clear that we should call that one "Kastle". Then, in 2004, the meeting was organized in a "Filmakademie" film school, so we called it "Akademy", and in 2005 we thought that it was important to keep the same name every year to build a brand, so we decided to name it "Akademy" just like the previous year, and it was named “Akademy” from then on.

Paul: And again history was made. Which has been your favorite Akademy so far?

Antonio: Always the coming Akademy! But of course I have a special fond memory of the one we organized in Malaga in 2005.

Paul: Almería is close to Málaga, so it may be just as good, right?

Antonio: I'm sure it'll be even better! We've learned a lot about organizing events since then.

Paul: Well, I for one look forward to your keynote. Thanks Antonio!

Antonio: Thanks to you for the interview.

Paul: It's a pleasure. See you in Almería.

Antonio: You can count on it.

About Akademy

For most of the year, KDE—one of the largest free and open software communities in the world—works on-line by email, IRC, forums and mailing lists. Akademy provides all KDE contributors the opportunity to meet in person to foster social bonds, work on concrete technology issues, consider new ideas, and reinforce the innovative, dynamic culture of KDE. Akademy brings together artists, designers, developers, translators, users, writers, sponsors and many other types of KDE contributors to celebrate the achievements of the past year and help determine the direction for the next year. Hands-on sessions offer the opportunity for intense work bringing those plans to reality. The KDE Community welcomes companies building on KDE technology, and those that are looking for opportunities. Join us by registering for the 2017 edition of Akademy today.

For more information, please contact the Akademy Team.